Jeremy Atherton Lin’s ‘Deep House’ Made Me Rethink What LGBTQ+ Music Is

From Max Freedman of Lavender Sound

Let’s Connect!

Instagram - Goodreads - Facebook - Bluesky - Threads - X - BookBub

🚨News & Announcements

Qstack Submissions are OPEN to everyone through December 31st!

Submit your articles, essays, editorials, flash/short stories, artwork and photography, poetry, interviews, and book/movie reviews—we are eager to see your work and publish it to our community of over 10,000 subscribers and followers. And remember that Qstack gladly accepts previously published work that you want more eyeballs on.

LINK to submission form and guidelines

I was so pleased when two of my favorite podcasters—K Anderson of Lost Spaces and John Parker of This Queer Book Saved My Life—teamed up for a recent episode of John’s other project, The Gaily Show, the only hour-long daily LGBTQ+ radio program in the U.S. (YouTube)

In the episode above, K shares about his newsletter, Queer Word, and a recent edition in which he revealed the ins/outs of the queer UK slang vocabulary “polari” which first came to our attention thanks to none other than—

—with the 1990 single “Piccadilly Palare” from His album Bona Drag.

Subscribe to Queer Word for all sorts of queer trivia, and check out their respective podcasts, starting with the episodes featuring your favorite Qstack host, MTF… 😘

➡️ The Hobbit with Troy Ford: This Queer Book Saved My Life

➡️ “I Can’t Imagine Not Being Gay” – with author Troy Ford: Lost Spaces

Check out WYATT! Out Loud’s latest podcast interview with Clarence A. Haynes, author of LGBTQ+ Fantasy debut, The Ghosts of Gwendolyn Montgomery. (YouTube)

“A superstar publicist has to contend with the literal ghosts of her past when they attempt to ruin her life in this debut novel… Haynes has created a mystical, sensuous, dangerous world of spirits and power while also making characters that feel three-dimensional and knowable… A smart, sexy story filled with ghosts, history, and resilience.” Kirkus Reviews

Got a big announcement, an article or event, a special offer, a new book published? MESSAGE me

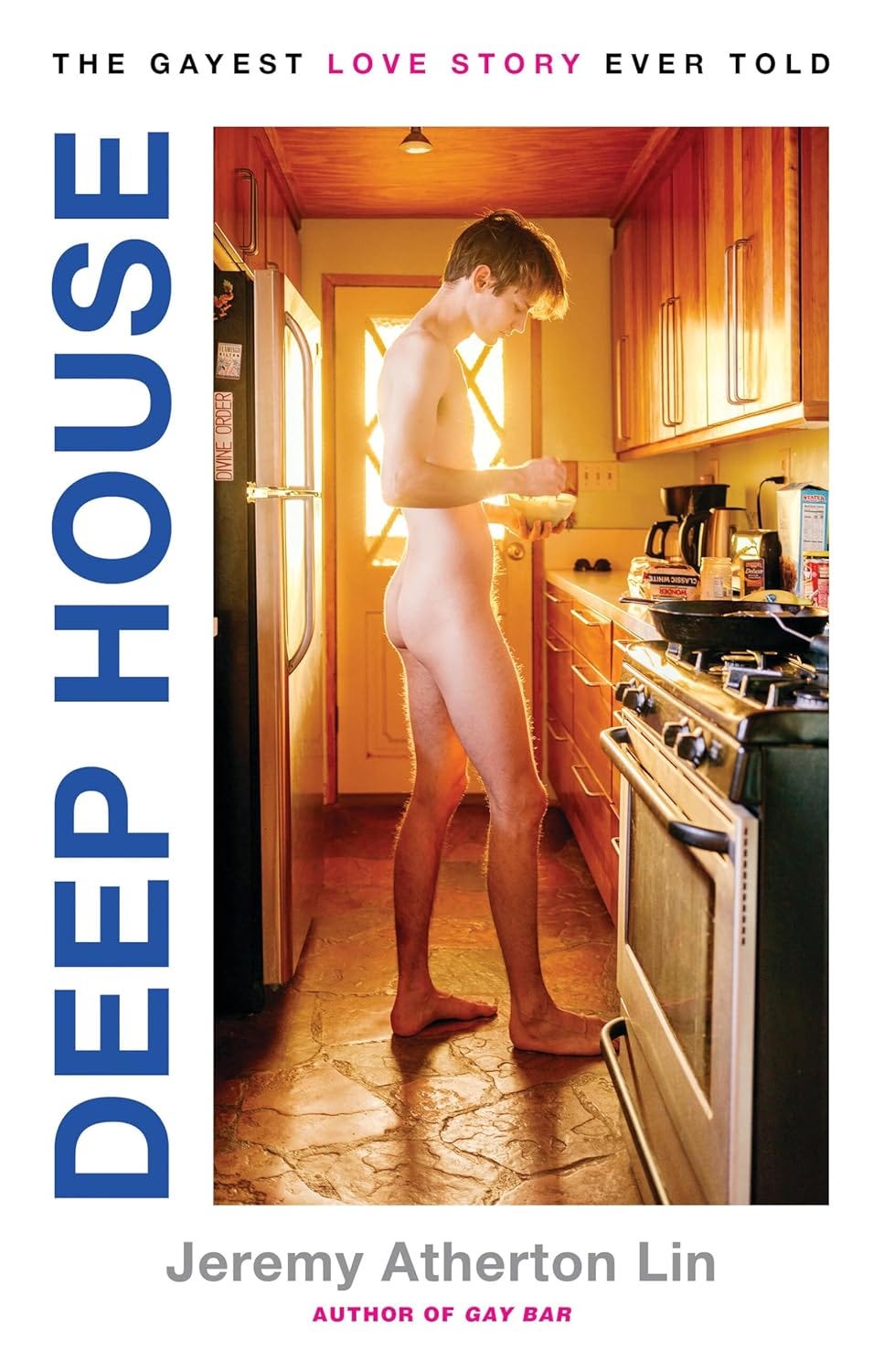

Jeremy Atherton Lin’s Deep House Made Me Rethink What LGBTQ+ Music Is

by Max Freedman of Lavender Sound

Not that you didn’t already know this, but news flash: Straight people love BRAT too (well, besides Taylor Swift, apparently). When the prominent YouTube music critic Anthony Fantano, who gave Charli XCX’s breakthrough album a rare perfect score, talked about Brat Summer with the inscrutable troll Adam Friedlander, the latter said something dismissive that was roughly, “Well, gay men had a great time.”

This one sentence perfectly summarizes the generally agreed-upon view of the music that LGBTQ+ folks (or at least gay men, non-binary AMAB folks, and the dolls) listen to: women in pop. It’s not just Charli XCX. There’s Cher, Madonna, Whitney. Beyoncé, Gaga, Sabrina, Chappell. Though a fair stereotype — gay men called themselves “friends of Dorothy” long before their broader queer acceptance in the public eye, though that’s rapidly on its way out in the U.S. — it vastly oversimplifies the breadth of excellent music that LGBTQ+ people enjoy. It posits that bubblegum melody, stellar singing, and the polish of major-label studio resources are superior to dirty, hissing rage and righteous dissonance. It posits that straightforwardness is acceptable listening and weirdness is to be scorned.

I run a publication, Lavender Sound, written by LGBTQ+ people about music that LGBTQ+ people listen to, and we run lots of stories about mainstream pop because of course we do, so I’m absolutely guilty of playing into this stereotype. It’s why I found Jeremy Atherton Lin’s second book, Deep House, so refreshing and mind-expanding when I read it in August 2025.

Nominally, Deep House is a book in which Lin simultaneously tells his own 1990s gay love story and recounts the history of the fight for gay marriage in the U.S. The completely unexpected thread that jumped out to me, though, is how often, amid his personal narrative, he name-drops musicians to set the scene — and they’re not the musicians you might expect from a cis gay man like Lin.

Yes, there’s a mention of Kelis’ “Milkshake” in the first sentence of a chapter titled “James Dean’s Penis.” But there’s also 1960s dad-rock stalwarts The Byrds; 1970s power-pop legends Big Star; and Stereolab and Blonde Redhead, which are, respectively, hipster ‘90s electronic and early-aughts rock favorites. Although I don’t care for The Byrds and I respect Big Star but they aren’t for me, I definitely felt seen by the Stereolab and Blonde Redhead mentions. It was like I was reading an actual friend’s diary, but with music, not everyday happenings, tracing their life.

None of these artists, of course, is widely viewed as part of the LGBTQ+ music canon. I mean, I’ve gone to shows put on by acts clearly inspired by Stereolab and Blonde Redhead and been completely surrounded by straight people. And yet, these are among the artists Lin weaves into his writing to magnify the details of what might seem like tiny moments but that, whether he’s wearing rose-colored or pitch-black glasses, feel pivotal to him. (I love his writing style; he balances straightforward narration with arrays of concise sentences that, like the music he loves, form a neat rhythm.)

Lin sets his own definition of LGBTQ+ music, and it couldn’t be simpler. If he likes it, then it’s music that LGBTQ+ people listen to. I want to get better at this myself. The first album my parents ever bought for me, at my request, was Spice, the debut Spice Girls album. But by the time I was in first or second grade, the other boys at summer camp were making fun of Britney Spears and anyone who liked her. I wanted to fit in, so I went along with it: No, of course I didn’t own …Baby One More Time. How could I? I was a real boy. (I was distinctly not; I’m agender and reject the word “man.”)

From then onward, I refused to associate myself with pop music by women, instead embracing rap and emo in middle school, grunge and heavy metal in early high school, and whatever Pitchfork was praising in late high school. My best friend at the time introduced me to Pitchfork when it was still more rockist than poptimist but kind of transitioning between the two, and he described it as, in different words, the music site with the correct opinions — the unquestionably correct opinions, the maker of music canon. Immersing myself in its work, the distance between myself and the pop music I grew up loving only expanded.

In college, I surrounded myself with friends who were generally of the Pitchfork-influenced music sphere and found myself immersed in noise rock. Think Deerhoof, whom I’m pretty sure Lin mentions in Deep House but I haven’t been able to find upon skimming through the pages again. Almost as a parody of whom I’d become, I began writing album reviews for Pitchfork in 2021, mostly about albums that — I didn’t realize this at the time, but I see it now — I thought would be cool to write about, not that I really had a passion for or on which I had a strong point of view. I now believe that I only liked some of the Pitchfork-y rock music I based my whole personality around (I say that with only mild exaggeration) to impress straight people. To distance myself from queerness. To turn my nose up at the consumption of art engineered by rooms full of people with potentially millions of dollars at their disposal (which doesn’t inherently make for bad art; far from it). To appear holier-than-thou. Informed. Smarter. Better.

It took me until I was nearly 30 to really, fully embrace pop music again and realize that my whole act from before was, of course, complete pretentiousness and performative superiority. As I caught up on the Gaga and Beyoncé albums I missed when I was sidelining pop music (but while still maintaining my love for Björk and Mitski, because duh), I realized how cordoned-off I became to my own emotions, my own joy, by scorning pop music instead of giving myself over to singing along, dancing, and letting the sticky hooks jolt every hair until it’s standing on end.

So, to see Lin embrace some of the artists I long associated with an effectively fraudulent version of myself reshaped my perspective. Was it okay to like the music I liked even if it wasn’t the kind of sound most associated with LGBTQ+ people? What if, even though I was putting on an act, I actually did like some of that music? What if I could love mainstream pop music and dissonant, off-kilter rock music mostly by and for straight people?

I started Lavender Sound to give LGBTQ+ people space to write about LGBTQ+ music, because lots of major publications’ writing about LGBTQ+ musicians (or artists with large LGBTQ+ fanbases) is by straight people, and because LGBTQ+ publications rarely cover music in-depth. I had a selfish ulterior motive, though: I never let myself write about pop music for the big publications I wrote for because, well, see above. It’s been a delight to do so for Lavender Sound, but Deep House has helped me realize that LGBTQ+ music can mean whatever I want it to mean, or whatever any LGBTQ+ person wants it to mean.

It’s why I’ve unashamedly written that Nine Inch Nails and Weyes Blood, two straight artists (the former especially so given Trent Reznor’s intense performance of masculinity), belong in the LGBTQ+ music canon. It’s why I entertained a pitch from a gay writer about the impact that Devo — four straight dudes in campy matching outfits, so arguably queer-coded — had on his life. It’s why I give as much space to Model/Actriz as to Madonna, to the noisy and the glamorous alike.

I was doing this before I read Deep House, but I had some trepidation about it. You see, I still regularly have this intrusive thought that, in spaces dominated by gay men, the dolls, and/or AMAB folks who may not be men but who present more masc than femme, if I name artists I listen to who aren’t in the mainstream, I’ll get a weird look, a gesture of confusion, perhaps even consternation. Lin’s writing reassured me that what matters most when talking or writing about music with people is that I genuinely have feelings about it — maybe I even love it — no matter who made it.

After reading Deep House, I’m finally able to present a take on Jay Som’s rock music as confidently as a review of JADE’s album. I’ve been able to go back to claustrophobic noise rock for the first time in three years without feeling like I’m betraying my queerness. I’ve been able to return to music scenes and friendships that, without saying so, I was kind of icing out because they didn’t feel queer enough.

Lin would support this; on Deep House, he embraces his somewhat left-field favorites while not at all scoffing at gay icons. There are two mentions of “The Happening” by The Supremes and one of Diana Ross herself. A friend of Lin’s advocates for Björk as a genius (I agree, of course). His partner often hears that the song by The Magnetic Fields, the cult indie rock band fronted by gay man Stephen Merritt, that most makes people think of him is “When My Boy Walks Down The Street.” Sure, Lily Allen and Amy Winehouse get namedrops, but so does Joan Armatrading, the seminal but overlooked lesbian folk-rock artist.

In Deep House, music isn’t a one-dimensional beast or a realm of exclusion. It’s a medium through which Lin, his partner, and their loved ones share moments together; the music itself matters far more than the gender or sexuality of its creator. For a long time, I thought that only genres associated with one set of genders and sexualities were valid, and then after that, I thought the same but about a different set of genders and sexualities. I’m grateful to Deep House for reminding me that inclusion doesn’t just mean making space for queer people and their art. It means being proud of who and what we love, no matter what.

Max Freedman (all pronouns) launched the LGBTQ+ music publication Lavender Sound to create an online writing community by and for LGBTQ+ people about LGBTQ+ music. They also interview artists for The Creative Independent, and they’ve previously contributed music criticism to Pitchfork, Bandcamp Daily, and Paste.